In India, the terms "Bofors scandal" and "2G scam" are synonymous with corruption, political intrigue, and monumental financial loss. For decades, these events have been etched into the public psyche as textbook examples of scams that tarnished the nation’s governance. But here’s the twist: the judiciary, after years of investigation and legal scrutiny, has told a different story—one that challenges the popular narrative. Despite the widespread belief that these were clear-cut cases of corruption, the facts and court rulings reveal a more nuanced reality. Let’s dive into the details and bust the misconceptions surrounding these two infamous episodes.

The Bofors Scandal: A Political Firestorm Without a Smoking Gun

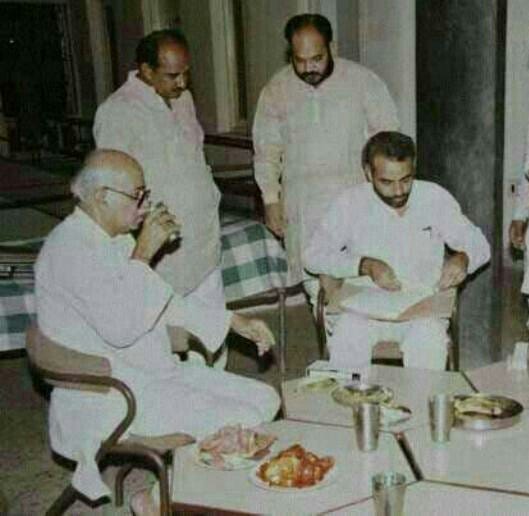

The Bofors scandal erupted in 1987 when Swedish Radio alleged that kickbacks were paid to secure a $1.4 billion deal for 410 field howitzers between the Indian government and the Swedish arms manufacturer AB Bofors. The accusations pointed fingers at high-profile figures, including then-Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, suggesting that bribes funneled through middlemen like Italian businessman Ottavio Quattrocchi tainted the deal. The political fallout was seismic—Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress party lost the 1989 elections, and the scandal became a symbol of corruption in Indian politics.

But what did the judiciary say? After nearly two decades of investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), the Delhi High Court delivered a pivotal ruling on February 4, 2004. Justice J.D. Kapoor stated that “16 long years of investigation by CBI could not unearth a scintilla of evidence” against the accused for accepting bribes or illegal gratification. The court quashed charges against key figures, including the Hinduja brothers, due to a lack of concrete proof. In 2018, the Supreme Court further dismissed a CBI appeal challenging the High Court’s decision, citing insufficient grounds to reopen the case after such a long delay.

The Bofors case unraveled not because of proven corruption but because of political sensationalism and media amplification. Allegations of secret Swiss bank accounts and shadowy middlemen fueled public outrage, yet no money trail was conclusively established. The narrative of a "scam" persisted, but the judiciary found no substance to back it up. Today, Bofors remains a cautionary tale—not of corruption, but of how unproven allegations can shape public perception for generations.

The 2G Spectrum Case: A “Scam” Built on Exaggeration

Fast forward to 2008, and the 2G spectrum case took center stage as India’s supposed "biggest scam." The controversy stemmed from the allocation of 122 telecom licenses by then-Telecom Minister A. Raja at 2001 prices, allegedly causing a staggering loss of ₹1.76 lakh crore ($25 billion) to the exchequer, according to the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG). The media and opposition parties painted a picture of rampant cronyism, with Raja accused of rigging the first-come-first-served policy to favor select companies in exchange for bribes. The public was incensed, and the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government faced a firestorm that contributed to its 2014 electoral defeat.

However, the judicial outcome flipped the script. On December 21, 2017, a special CBI court acquitted all 19 accused, including A. Raja and DMK MP Kanimozhi, after a seven-year trial. Special Judge O.P. Saini’s 1,552-page verdict was scathing: “Some people created a scam by artfully arranging a few selected facts and exaggerating things beyond recognition to astronomical levels.” The court found no evidence of criminality or conspiracy in the spectrum allocation process. It criticized the CBI’s case as relying on “rumor, gossip, and speculation,” noting that the prosecution failed to prove any bribery or financial loss.

The ₹1.76 lakh crore figure, often cited as gospel, was a notional estimate—not a proven loss. The Supreme Court had canceled the licenses in 2012, citing procedural irregularities, but this didn’t equate to evidence of corruption. Subsequent spectrum auctions under the BJP government fetched far less than the CAG’s projection, further undermining the "scam" narrative. In March 2024, the Delhi High Court admitted a CBI appeal against the acquittal, acknowledging contradictions in the trial court’s judgment that warrant deeper scrutiny. Yet, as of now, no court has overturned the 2017 ruling, leaving the "2G scam" as a case of perception outpacing proof.

Why the Misconception Persists

So why do Indians still view Bofors and 2G as undeniable scams? The answer lies in a mix of political opportunism, media sensationalism, and a public appetite for outrage. In both cases, opposition parties leveraged the allegations to devastating effect—Bofors toppled Rajiv Gandhi, and 2G fueled Narendra Modi’s 2014 wave. The media, too, played a role, amplifying unverified claims and eye-popping figures like ₹1.76 lakh crore, which stuck in the collective memory. Over time, these narratives hardened into "facts," even as the judiciary found no evidence to sustain them.

There’s also a deeper cultural factor at play: a pervasive distrust of politicians and institutions. In a country where corruption is a lived reality for many, it’s easy to assume the worst. But assuming guilt isn’t the same as proving it—and that’s where the courts come in.

The Judicial Reality Check

The judiciary’s role in both cases is a reminder that allegations aren’t evidence. For Bofors, the Delhi High Court and Supreme Court found no proof of bribery after exhaustive probes. For 2G, the special court dismantled the prosecution’s case, calling it baseless, while the ongoing appeal process has yet to reverse that finding. These rulings don’t mean irregularities didn’t occur—Bofors had murky middlemen, and 2G’s allocation process was flawed—but they do mean that the label "scam" doesn’t hold up under legal scrutiny.

Time to Rethink the Narrative

The Bofors scandal and 2G spectrum case have shaped India’s political landscape, but they’ve also distorted its understanding of corruption. The misconception that these were proven scams ignores the judicial outcomes and the absence of hard evidence. It’s time to shift the conversation from reflexive outrage to critical reflection. Corruption is real and must be fought, but not every controversy is a scam—and not every accusation is a fact.

As Indians, we owe it to ourselves to question the stories we’ve been told. The next time someone brings up Bofors or 2G, ask them: What did the courts say? The answer might surprise you—and it might just change the way you see India’s so-called "biggest scams."