The Carrot of Caste Census and the Stick of Anti-Reservation Propaganda

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the user alone and are shared here for discussion purposes only. No legal liability is assumed, and readers are encouraged to form their own judgments based on independent research.

In the intricate chessboard of Indian politics, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) appears to be employing a classic carrot-and-stick strategy when it comes to caste dynamics and affirmative action. On one hand, the party has dangled the promise of India’s first comprehensive public caste census since independence, slated to begin in 2027, as a sweetener to woo lower-caste voters.

On the other, a surge in anti-reservation rhetoric — often amplified by the BJP’s IT cell and affiliated social media handles — seems designed to stoke resentment among upper castes and dilute demands for expanded affirmative action once the census results emerge. This duality raises questions about the party’s long-term intentions: Is this a genuine step toward social justice, or a tactical maneuver to maintain power without upsetting its traditional upper-caste base?

The Carrot: Promising a Long-Awaited Caste Census

The BJP-led central government announced in June 2025 that the 16th national census, delayed multiple times due to the COVID-19 pandemic, would commence on March 1, 2027, and for the first time in nearly a century, include a detailed enumeration of castes. This move, described by sources as focusing on “caste, not class,” requires individuals to declare their caste and religion, marking a significant shift from previous censuses that only tracked Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). The process is set to unfold in two phases, with data collection wrapping up by 2030 — conveniently after the 2029 Lok Sabha elections.

For lower-caste communities, including Other Backward Classes (OBCs), SCs, and STs, this census represents a potential game-changer. It could provide empirical data to address longstanding disparities, potentially justifying demands for increased reservations in education, jobs, and even the private sector. BJP leaders have positioned this as a fulfillment of social justice commitments, with party campaigns in states like Uttar Pradesh emphasizing it as a tool for equitable representation. Critics from opposition parties, such as the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), have claimed credit for pressuring the government into this decision, but the BJP has framed it as a proactive step under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership.Heading into the 2029 elections, this announcement could serve as a powerful electoral carrot. The party might rally lower-caste voters by highlighting its role in conducting the census, portraying it as a pathway to “equitable representation.” Gullible or hopeful sections of these communities might buy into the narrative, believing that post-census reforms will follow. However, with results not expected until 2030, any substantive changes — like raising the 50% reservation cap or introducing private-sector quotas — would come after the polls, allowing the BJP to secure votes without immediate commitments.

The Stick: Fanning Anti-Reservation Flames on Social Media

Contrasting sharply with this promise is the relentless anti-reservation propaganda flooding social media platforms, particularly X (formerly Twitter), which has intensified since late 2024 and early 2025 — coinciding suspiciously with the census announcement. BJP-affiliated accounts and IT cell operatives have been accused of amplifying content that blames reservations for everything from infrastructure failures to societal ills, reaching what many describe as “delusional levels.”

Examples abound: In one viral incident, an Indian-American professor sparked outrage by attributing a deadly Air India crash to India’s reservation policies, claiming “freeloaders are more important.” Social media posts link reservations to brain drain, with users lamenting that talented individuals flee abroad due to “unfair” quotas. Even mundane issues like potholes or bridge collapses are absurdly pinned on affirmative action, as if meritocracy alone could pave roads or build sturdy infrastructure. X searches reveal a pattern: Queries for “anti reservation” or “blame reservation” yield posts tying quotas to unrelated crises, often with high engagement and from accounts echoing BJP narratives.

This rhetoric isn’t organic; it’s amplified by organized efforts. Reports from 2024–2025 highlight a spike in hate speech and divisive content on social media, peaking during elections and policy announcements. BJP IT cell members have been caught sharing edited videos or misleading claims to portray opposition leaders as anti-reservation, while subtly undermining the system itself. The pace has quickened post-census reveal, suggesting a deliberate strategy to desensitize the public to quota demands. By 2030, when census data might reveal stark inequalities, the ground could be prepared for upper-caste outrage to suppress calls for reform, ensuring the status quo persists.

The Underlying Realities: Persistent Backwardness Among SC/ST/OBC

This speculated strategy hinges on ignoring — or downplaying — the harsh realities faced by SCs, STs, and OBCs, who remain economically backward and under-represented despite decades of reservations. Data from recent surveys paints a grim picture.

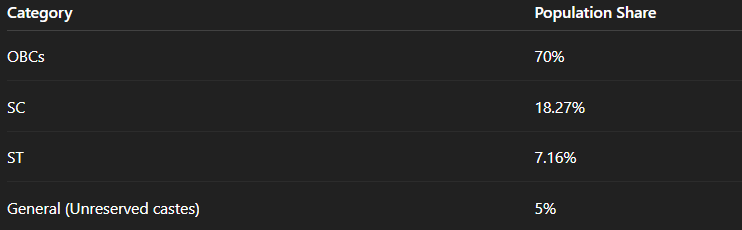

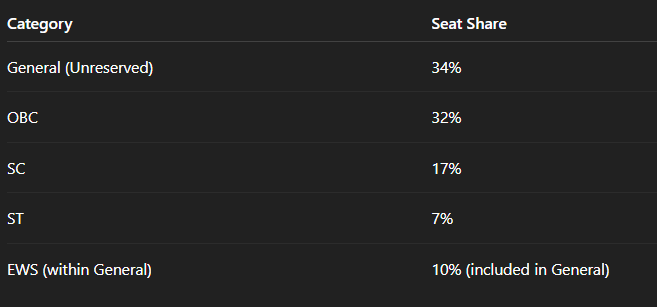

Economically, these groups lag significantly. In Bihar’s 2023 caste survey (a precursor to the national one), OBCs and Extremely Backward Classes comprised 63% of the population but faced disproportionate poverty. Nationally, indicators from the Mandal Commission and recent reports show higher poverty rates among SC/ST/OBC, with limited access to quality education and jobs. For instance, systemic exclusion manifests in “deep-rooted deprivation,” as argued in a Madhya Pradesh Supreme Court affidavit defending OBC quotas. Estimates suggest that if the census confirms 75–80% of Indians belong to backward classes, demands for breaching the 50% quota cap could intensify — but only if propaganda doesn’t preempt them.Under-representation is equally stark. In central government jobs, OBCs hold about 22% of positions as of 2022–23, below the 27% mandate, while SCs and STs often fill lower-rung roles but remain below 11% and 5% in teaching posts, respectively. Thousands of reserved vacancies go unfilled annually, signaling inequality rather than abundance. In private higher education institutions, representation of marginalized students is “abysmal,” with calls for mandatory quotas unmet. Population-wise, OBCs, SCs, and STs make up over 70% of India, yet their share in elite jobs and education doesn’t reflect this.

BJP’s Balancing Act: Appeasing Bases Without Real Change

Historically backed by upper castes, the BJP has expanded its reach among OBCs and lower castes through figures like Modi (an OBC himself). Yet, this carrot-and-stick approach suggests a desire to placate lower castes with symbolic gestures like the census while using propaganda to ensure upper-caste “savarna” outrage mutes any push for meaningful reforms. In an ideal scenario for the party, the census proceeds, but demands for private-sector reservations or quota hikes are drowned out by anti-reservation noise.

This speculation isn’t without precedent. Past BJP moves, like lateral entry in civil services or privatization drives, have been criticized as anti-reservation. If the pattern holds, the 2027 census could be a masterstroke: Win 2029 votes with promises, then leverage built-up resentment to stall action by 2030.

Ultimately, this strategy risks alienating both sides if exposed. Lower castes might see through the delay tactics, while upper castes grow wary of endless appeasement. As India hurtles toward 2029, the true test will be whether this duality fosters unity or deepens divisions. For now, the carrot dangles enticingly, but the stick looms large.