When Privilege Gets Help, It’s “Networking”; When Others Get Help, It’s “Quota”

Unpacking the Double Standards of Caste Privilege in India

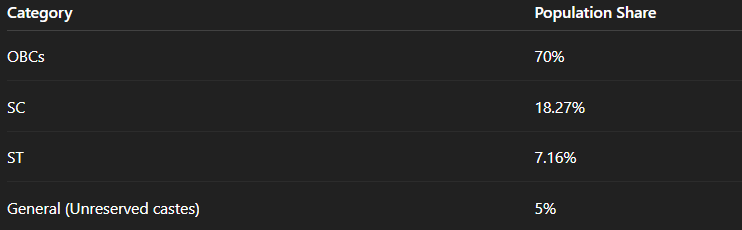

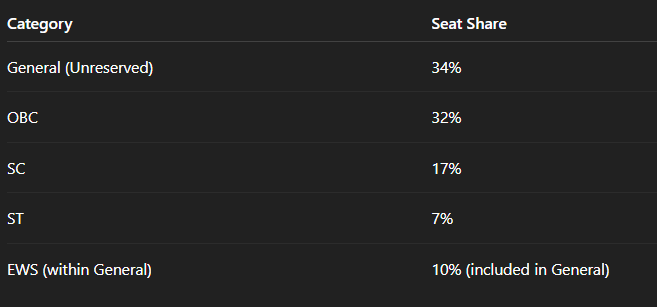

In India, the conversation around social mobility often reveals a stark hypocrisy. For those in the “general category” — a polite euphemism for upper castes — opportunities handed down through family ties, alumni networks, or social circles are celebrated as savvy “networking.” It’s seen as a natural extension of merit, hard work, and personal connections. But when lower castes, including Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC), access affirmative action through reservations or quotas, it’s frequently demonized as unfair favoritism, a handout that undermines true achievement. This double standard isn’t just rhetoric; it’s rooted in centuries of systemic inequality that continues to shape Indian society today.

This article delves into how upper castes justify their privileges as legitimate networking while vilifying quotas for others. We’ll trace the historical factors that built these upper-caste networks from ancient times and explore why lower castes have been systematically denied the same advantages. Drawing from historical context and contemporary analyses, the goal is to highlight how caste operates as an invisible force, often unacknowledged by those who benefit from it most.

The Myth of Merit: How Upper Castes Frame Privilege as “Networking”

Upper castes in India have long positioned their advantages as the fruits of individual effort and strategic connections, rather than inherited privilege. For instance, in professional fields like tech, finance, and academia, upper-caste individuals often leverage family legacies, elite school alumni groups, and informal referrals to secure jobs or promotions. This is praised as “networking” — a skill anyone can supposedly learn. Yet, as discussions on platforms like Reddit point out, these networks are rarely accessible to outsiders, and they’re built on generations of exclusivity.

A key justification is the narrative of “meritocracy.” Upper castes argue that their success stems from superior education and skills, ignoring how caste has historically monopolized access to these resources. In the tech industry, for example, upper-caste dominance in Silicon Valley and Indian IT firms is often attributed to talent, but research shows it’s largely due to early migration waves favoring those with pre-existing privileges like English education and urban connections.

This framing allows privilege to hide in plain sight: when a Brahmin or Kshatriya gets a leg up from a relative in a high position, it’s “using connections wisely.” Meanwhile, quotas are labeled as “reverse discrimination,” eroding standards.

This hypocrisy extends to everyday discourse. Upper-caste individuals might dismiss caste as irrelevant in modern India, claiming society is now “casteless” for the privileged. But as one analysis notes, this invisibility is itself a privilege — upper castes don’t “see” caste because it works in their favor, maintaining homogeneity in elite spaces like universities and corporations.

Studies from higher education institutions reveal that upper-caste students often view their advantages as earned, while perceiving lower-caste peers as undeserving beneficiaries of quotas.

Demonizing Quotas: The Backlash Against Lower-Caste Support

On the flip side, affirmative action programs — designed to counteract centuries of exclusion — are routinely attacked as unjust. The 10% quota for economically weaker sections (EWS) among upper castes, introduced in 2019 and upheld in 2022, sparked outrage from activists who argued it further entrenches privilege by benefiting those already advantaged, while diluting reservations for historically oppressed groups. Critics from lower castes see this as a “violation” of constitutional equity, yet upper castes frame it as a fair extension of economic aid.

The demonization often boils down to resentment: quotas are portrayed as “stealing” opportunities from the “meritorious.” In media and social commentary, lower-caste success via reservations is dismissed as tokenism, ignoring the barriers they overcome. For example, in science and academia, upper castes dominate due to inherited networks, but quotas for lower castes are blamed for any perceived drop in quality.

This narrative conveniently overlooks how upper-caste “networking” functions as an unofficial quota system, reserving spots through referrals and social capital.

In essence, when lower castes get institutional help, it’s seen as charity at the expense of others. But upper-caste networking? That’s just business as usual.

From Ancient Roots: The Historical Foundations of Upper-Caste Networking

The origins of this disparity trace back to India’s ancient caste system, formalized in texts like the Manusmriti around 200 BCE to 200 CE. This varna system divided society into four hierarchical groups: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (traders), and Shudras (laborers), with Dalits (formerly “untouchables”) outside it entirely. Upper castes, particularly Brahmins, were granted exclusive rights to education, land ownership, and religious authority, creating early networks of power.

Over centuries, these structures evolved under various rulers, from medieval kingdoms to British colonialism. Upper castes adapted by aligning with colonial administrators, gaining access to English education and civil service roles. This built intergenerational wealth and connections: families passed down knowledge, property, and social ties, forming closed networks in bureaucracy, business, and academia.

In the modern economy, these networks persist. In Mumbai’s industrial era, upper castes used caste-based associations to secure jobs in mills and factories. Today, in global migration, upper castes dominate tech and professional diasporas because historical privileges like better schooling and urban access enabled them to capitalize on opportunities first. Economic studies show Brahmins enjoy higher education, income, and social connections, reinforcing their networks.

Caste-based segregation in cities further cements this, with upper castes clustering in affluent areas for mutual benefit.

These factors — rooted in ancient hierarchies and amplified through history — have created a self-perpetuating system where upper castes “network” effortlessly, often without recognizing it as privilege.

Barriers to Entry: Why Lower Castes Don’t Have the Same “Networking” Privileges

Lower castes have been systematically excluded from building similar networks due to entrenched discrimination and resource deprivation. Historically, they were barred from education, property ownership, and social mixing, enforced through untouchability and violence. This legacy persists: lower castes face poorer schools, underfunded institutions, and exclusion from elite networks.

Economically, caste restricts access to finance and entrepreneurship. Dalits and OBCs encounter discrimination in hiring, loans, and business partnerships, limiting their ability to form robust networks. In rural areas, landlessness and manual labor trap generations in poverty, while urban migration favors those with prior advantages — often upper castes.

Socially, caste homogeneity in elite spaces makes integration difficult. Lower castes report invisibility or outright bias, with upper castes refusing to collaborate or mentor. During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, lower castes suffered disproportionately due to lack of safety nets and networks. Macroeconomic analyses estimate that caste discrimination reduces entrepreneurial potential and overall growth, as lower castes are denied the capital and connections upper castes take for granted.

In short, lower castes aren’t just starting from behind; the system is rigged to keep them there, without the “networking” luxuries afforded to others.

Toward a More Equitable Future

Recognizing this double standard is the first step toward dismantling it. While quotas provide essential redress, true equity requires addressing the invisible networks that perpetuate upper-caste dominance. As India evolves, conversations around caste must move beyond denial to acknowledgment — only then can networking become a tool for all, not just the privileged few.By examining these dynamics, we see that privilege isn’t always overt; it’s often woven into the fabric of society. For a nation aspiring to meritocracy, confronting caste head-on is non-negotiable.