India’s Sexism: A Deep-Rooted Dance of Power and Progress

India dazzles — 1.4 billion people, a kaleidoscope of cultures, and a global tech titan. Yet beneath the shimmer lies a shadow: sexism, woven into its fabric through centuries of patriarchy, religion, and social norms. It’s not just overt violence — think rape cases grabbing headlines — but the quieter, pervasive biases that shape daily life. From rural dowry deaths to urban boardroom snubs, sexism in India is a hydra, multi-headed and stubborn. Let’s unpack its origins, how it plays out, and where change is stirring.

The Historical Backbone: Patriarchy’s Long Game

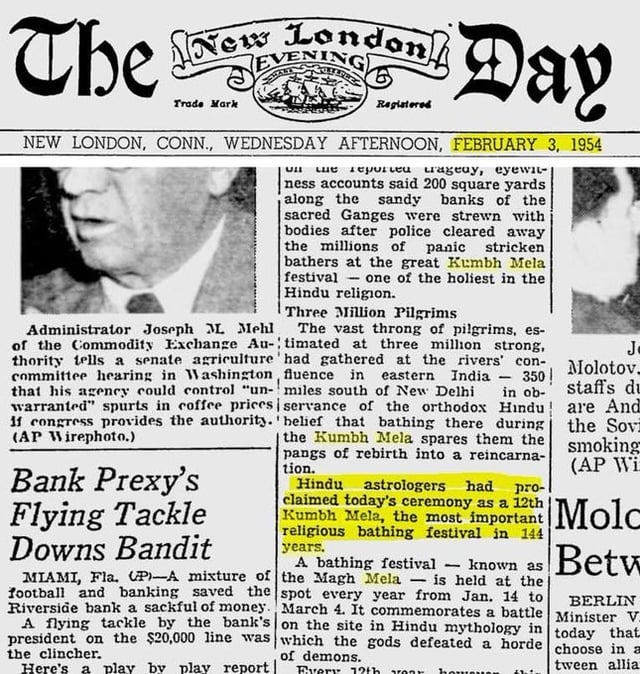

Sexism in India didn’t spring up overnight. The Vedic era (1500 BCE) praised goddesses — Saraswati, Durga — yet relegated women to domesticity in texts like the Manusmriti, which declared a woman’s duty as obedience to her father, husband, then son. By medieval times, practices like sati (widow immolation) and purdah (seclusion) cemented control over women’s bodies and agency. The Mughal era added harems; colonial British rule outlawed sati (1829) but reinforced “civilizing” gender norms — think Victorian modesty over Indian fluidity.

Fast forward: 70% of Indians still see tradition as sacred (Pew, 2021), and that reverence often props up old power structures. Dowry, banned in 1961, persists — 95% of rural marriages involve it (World Bank, 2022). History’s echo lingers — sexism isn’t an anomaly; it’s an inheritance.

Everyday Sexism: From Homes to Streets

In homes, it’s subtle but steel-clad. Nine in ten Indians agree a wife must obey her husband (Pew, 2022) — a norm cutting across class and caste. Sons inherit; daughters marry out, often with dowry baggage — 8,233 deaths reported in 2012 alone (NCRB). Women spend six times more hours on unpaid chores than men (Oxfam, 2023), a burden urban “modernity” barely dents.

On streets, it’s louder — catcalls, groping, or worse. One in five women face frequent public harassment (Psychological Science, 2024); 24,923 rapes were reported in 2012 (NCRB), though untold numbers stay silent. The 2012 Delhi gang rape — Nirbhaya — sparked outrage, yet 428,278 crimes against women hit a record in 2021 (NCRB). Why? Stigma, police apathy (98% of rapists known to victims), and a culture where 40% of women and 38% of men justify spousal abuse (NFHS-5).

Workplaces mirror this. Tech, India’s pride (36% female workforce, NASSCOM), still dishes out microaggressions — cake-cutting falls to women, heels draw snark (Rest of World, 2022). The pay gap yawns — 38% in IT (Monster, 2016) — and glass ceilings loom. Only 25% of women are in formal jobs (UNICEF), hemmed by “family duty.”

Cultural Fuel: Myths and Media

Sexism feeds on narratives. Benevolent sexism — “women are pure, needing protection” — sounds sweet but shackles. A 2024 study (Psychological Science) found it cuts tolerance for street harassment but boosts acceptance of domestic violence — 92% of Indians hold at least one bias against women’s autonomy (UNDP, 2023). Hostile sexism — “women seek power over men” — justifies outright aggression.

Bollywood doesn’t help. Heroines twirl around heroes; item songs objectify. TV soaps glorify submissive bahus (daughters-in-law). Ads peddle fairness creams — 70% of women feel pressured to lighten skin (Nielsen, 2022) — tying worth to looks. Yet cracks show: films like Pink (2016) and Thappad (2020) call out consent and abuse.

Regional Riffs: Not One India

Sexism shifts by region. Kerala boasts 96% female literacy (NFHS-5) and matrilineal traces, yet 25% of its youth are jobless (CMIE, 2023) — education doesn’t equal freedom. Tamil Nadu’s Dravidian pride resists Hindi patriarchy, but domestic violence persists. The Northeast — Assam, Meghalaya — offers tribal autonomy (99% female decision-making, Banerjee, 2015), yet 52% see widespread gender bias (Pew, 2022). Hindi Belt states like Uttar Pradesh lag — 6% report discrimination (Pew), but dowry and honor killings spike (NCRB).

The Pushback: Laws, Voices, Limits

India fights back. The Constitution guarantees equality (Article 14); laws ban dowry, sati, sex-selective abortion. Post-Nirbhaya, rape penalties stiffened — minimum seven years, up to life (2013). Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao (Save the Girl, Educate the Girl) cut female feticide, nudging the sex ratio to 1,020 women per 1,000 men (NFHS-5, 2021).

Women rise — Indira Gandhi ruled in 1966; today, 55% say women match men as leaders (Pew, 2022). The #MeToo wave hit India in 2018 — journalists, actors named abusers. X buzzes with feminist calls; NGOs like Survival Instincts teach self-defense. Yet, gaps yawn — 16% of women report personal discrimination (Pew, 2020), and India ranks 135th in global gender parity (WEF, 2023). Laws falter without cultural shift.

Why It Sticks, Where It’s Cracking

Sexism endures because it’s systemic — patriarchy’s a safety net for power. Poverty (20% below $2.15/day, World Bank) and illiteracy (26% of women, NFHS-5) trap millions. Religion — Hindu, Muslim, Sikh — can sanctify norms; 63% prioritize sons for rites (Pew, 2022). But cracks widen — urban women delay marriage (35% single at 25–34, NFHS-5), tech amplifies voices, and education chips at biases.

The Road Ahead

India’s sexism is a paradox — progress and prejudice tangled tight. It’s not just Delhi’s rapes or Bihar’s dowries; it’s the auntie tsk-ing a girl’s shorts, the boss bypassing her promotion. Change needs more — men rethinking “protection,” media ditching tropes, laws biting harder. India’s not alone — global sexism simmers — but its scale and stakes (half a billion women) make it urgent. The dance isn’t over; the rhythm’s just shifting.