The Selective Lens of Hindu Nationalism: Ignoring Dalit Oppression in Historical Narratives

The Hindu Nationalist Historical Narrative

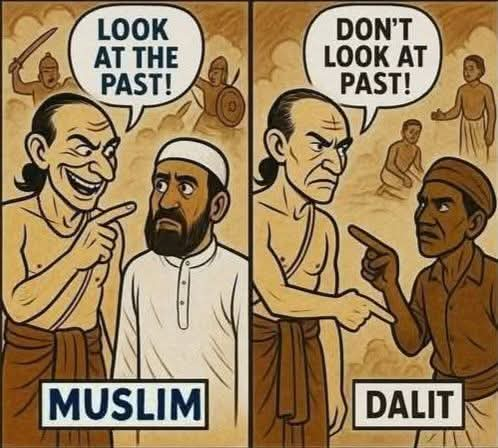

Hindu nationalism, as propagated by organizations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliates, often portrays Indian history as a saga of Hindu victimhood under Muslim rule, particularly during the Mughal era. This narrative highlights events like temple destructions or forced conversions, framing Muslims as perpetual aggressors against a monolithic Hindu identity. While historical instances of conflict between Hindu and Muslim rulers are undeniable, this framing deliberately oversimplifies India’s complex past, ignoring the diversity of Hindu society and its internal hierarchies.

What is conspicuously absent from this narrative is any acknowledgment of the caste system’s role in oppressing millions of Dalits, who were relegated to the margins of society long before the arrival of Muslim rulers. By fixating on external “invaders,” Hindu nationalists deflect attention from the internal systemic injustices that have defined Hindu social order for centuries.

The Millennia-Long Oppression of Dalits

The caste system, deeply embedded in Hindu social and religious practices, has systematically marginalized Dalits (formerly referred to as “untouchables”) for over two thousand years. Ancient texts like the Manusmriti codified discriminatory practices, prescribing harsh punishments for lower castes who dared to transgress their assigned roles. Dalits were deemed impure, their touch or even shadow considered polluting by upper-caste Hindus. These beliefs were not isolated but institutionalized, shaping social interactions, economic opportunities, and religious access.

Historical accounts, such as those by the Chinese traveler Faxian (Fa-Hsien) during the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE), describe the plight of the Chandalas, a lower-caste group forced to live outside villages and announce their presence to avoid “polluting” others. This is not a relic of the distant past; discriminatory practices persisted into the modern era. Dalits were barred from temples, forbidden from drawing water from village wells, and subjected to humiliating customs like the “breast tax” in parts of South India, where lower-caste women were forced to pay to cover their bodies. These practices were not imposed by Muslim rulers but were enforced by upper-caste Hindus, who held social and religious authority.

Even today, the legacy of caste oppression endures. Manual scavenging, a dehumanizing practice where individuals (overwhelmingly Dalits) clean human waste from dry latrines, remains a stark reminder of caste-based exploitation. Despite legal bans, reports estimate that over 1.3 million Dalits are still engaged in this work, facing social stigma and health risks. Hindu nationalist discourse rarely addresses these modern injustices, focusing instead on historical grievances against Muslims or contemporary issues like “love jihad.”

Why Hindu Nationalists Avoid the Dalit Question

The reluctance of Hindu nationalists to confront caste oppression stems from both ideological and strategic considerations. Ideologically, their vision of a unified Hindu identity requires downplaying internal divisions like caste, which fracture the notion of a cohesive “Hindu nation.” Acknowledging the historical and ongoing oppression of Dalits would force a reckoning with the role of upper-caste Hindus in perpetuating this system, undermining the narrative of Hindu victimhood.

Strategically, Hindu nationalism relies on mobilizing a broad Hindu voter base, including Dalits, to counter perceived threats from minorities. Admitting the historical guilt of upper-caste oppression risks alienating Dalit communities, who have increasingly asserted their rights through movements inspired by leaders like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. Instead, Hindu nationalist rhetoric often co-opts Dalit identity, portraying them as part of the Hindu fold while ignoring their specific grievances. This tokenism is evident in the selective celebration of Ambedkar as a Hindu icon, while his critiques of caste and Hinduism are conveniently ignored.

The Consequences of Selective History

This selective reading of history has profound implications. By focusing on Muslim oppression while ignoring caste-based atrocities, Hindu nationalists perpetuate a distorted understanding of India’s past that fuels communal tensions. This narrative not only marginalizes Dalits but also erases the contributions of lower-caste reformers who fought against caste oppression, from Jyotirao Phule to Periyar.

Moreover, it distracts from addressing contemporary issues like manual scavenging, caste-based violence, and discrimination in education and employment. According to a 2020 report by the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights, over 40% of Dalit households in rural India still face untouchability practices, such as being denied access to public spaces or services. These are not relics of a distant past but ongoing realities that Hindu nationalist discourse sidesteps.

Toward a More Honest Historical Reckoning

A balanced understanding of Indian history requires acknowledging both external conflicts and internal injustices. The oppression of Dalits is not a peripheral issue but a central feature of India’s social history, one that predates and outlasts Muslim rule. Hindu nationalists must confront the uncomfortable truth that upper-caste Hindus were complicit in a system that dehumanized millions for millennia. Only by addressing this can India move toward a more inclusive national identity that honors all its citizens.

This is not to diminish the complexities of Hindu-Muslim relations or the historical realities of invasions and conquests. But a singular focus on one form of oppression while ignoring another is not just selective — it’s dishonest. True nationalism should uplift the marginalized, not erase their suffering. Until Hindu nationalists engage with the full spectrum of India’s history, including the painful legacy of caste, their vision of a unified nation will remain incomplete.