The Shadow of Karma: How an Ancient Doctrine Cemented Centuries of Suffering for India’s Untouchables

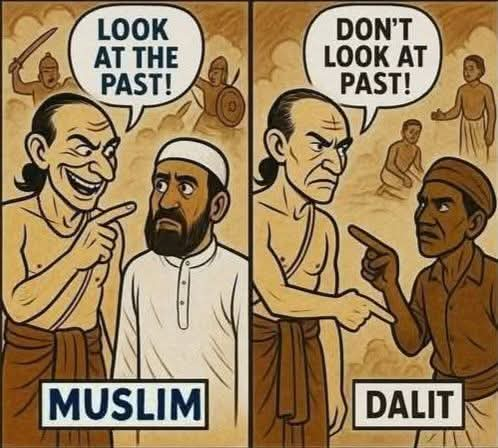

In the labyrinth of India’s social history, few concepts have wielded as much power — and inflicted as much pain — as the theory of karma. For millennia, this philosophical pillar of Hinduism has been invoked to explain, and often justify, the rigid hierarchies of the caste system. At the bottom of this pyramid lay the “untouchables,” now known as Dalits, whose lives of destitution, discrimination, and dehumanizing labor were framed not as societal failures, but as cosmic consequences. Imagine being told that your poverty, your exclusion from temples, and even the violence inflicted upon you are all deserved — payments for sins committed in a life you can’t remember. This is the insidious logic that karma imposed on millions, turning oppression into divine decree.

But how did this happen? How did a idea meant to encourage moral living become a tool for perpetuating inequality? In this exploration, we’ll unpack the historical and philosophical threads that wove karma into the fabric of untouchability, revealing a system so entrenched that even its victims often accepted it as fate.

The Foundations: Caste and Karma in Ancient India

India’s caste system, one of the world’s oldest forms of social stratification, traces its roots back to the Vedic period around 1500 BCE. Described in the Rig Veda, society was initially divided into four varnas (classes): Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (laborers). Outside these varnas were the outcastes, or untouchables — groups deemed so impure that contact with them was believed to pollute higher castes. These untouchables, often indigenous tribes or defeated communities, were relegated to the fringes of society, performing the most menial and degrading tasks, like cleaning sewers, handling dead bodies, or manual scavenging.

Enter karma, a core tenet of Hindu philosophy derived from the Upanishads (circa 800–200 BCE). Karma posits that every action — good or bad — generates consequences that carry over into future lives through reincarnation (samsara). The cycle of birth, death, and rebirth continues until one achieves moksha (liberation), breaking free from this wheel.

In theory, it’s a system of cosmic justice: live righteously, and you’ll reap rewards in the next life.But in practice, karma was twisted to reinforce birth-based hierarchies. Texts like the Chandogya and Kaushitaki Upanishads linked one’s rebirth to past deeds, suggesting that good karma led to birth in higher varnas, while bad karma resulted in lower ones — or worse, as an untouchable.

The Manusmriti, an influential legal text from around 200 BCE to 200 CE, codified this by prescribing harsher punishments for lower castes and restricting their access to education, property, and rituals. Thus, an untouchable’s suffering in this life wasn’t random; it was penance for sins in a previous existence.

Justifying the Unjust: Suffering as Deserved Fate

This linkage created a powerful narrative: If you’re born an untouchable, it’s because of your own past misdeeds. Your current hardships — poverty, social isolation, and backbreaking labor — are not the fault of the upper castes or the system, but a direct result of your soul’s history. Upper castes, conversely, enjoyed their privileges as rewards for prior virtue, giving them a moral license to maintain the status quo.

The doctrine went further by tying karma to dharma (duty). For untouchables, salvation lay in faithfully performing their assigned roles — no matter how degrading. Manual scavenging, for instance, was seen as their dharma; by enduring it without complaint, they could accumulate good karma, potentially earning a higher birth in the next life and eventual moksha. The Bhagavad Gita reinforces this in verses like 18:47, stating that it’s better to perform one’s own dharma imperfectly than another’s well, implying that straying from caste duties invites more bad karma.

This framework didn’t just justify exploitation; it sanctified it. Untouchables were barred from entering temples, drawing water from common wells, or even casting shadows on higher castes, all under the guise of preserving ritual purity. Violence against them, including beatings or killings for “transgressions,” was rationalized as upholding cosmic order. For thousands of years, from the Vedic era through medieval times and into colonial India, this ideology held sway, ensuring social stability at the expense of human dignity.

The Tragic Acceptance: Internalization and Brainwashing

Perhaps the most heartbreaking aspect is how untouchables themselves internalized this belief. Through generations of religious indoctrination, many came to view their plight as self-inflicted, a form of radicalization that turned victims into unwitting enforcers of their own oppression. System Justification Theory in psychology explains this: Believing in karma provides a sense of certainty and security, making unbearable suffering feel meaningful rather than arbitrary. It fosters low self-esteem and diminished aspirations, perpetuating the cycle without needing overt coercion.

This brainwashing was amplified by religious leaders and texts. Shankaracharya of Puri, a prominent Hindu figure, emphasized that caste (jati) is determined by birth alone, not actions, to preserve “pure” lineages. Untouchables were taught that rebellion would only worsen their karma, dooming them to even lower rebirths. Even today, echoes of this persist in rural India, where Dalits sometimes accept discrimination as fate, despite constitutional protections.

Breaking the Cycle: Lessons for Today

The story of karma and untouchability is a cautionary tale about how philosophies can be co-opted to serve power. It reminds us that true justice requires questioning inherited beliefs, not accepting them as destiny. As India evolves, shedding these shadows could pave the way for a society where birth doesn’t dictate worth — and where karma inspires personal growth, not perpetual chains.