Bal Gangadhar Tilak is widely celebrated as one of the foremost leaders of India’s early nationalist movement. Revered as “Lokmanya” (beloved of the people), he played a vital role in awakening political consciousness among Indians and popularizing the idea of Swaraj (self-rule). However, while his contributions to the independence struggle are undeniable, his views on social issues—particularly regarding women, caste, and reform—remain deeply problematic.

This article seeks to highlight and critically examine some of the more questionable positions Tilak held, as recorded in his writings and political interventions.

1. Opposition to the Age of Consent Act (1891)

Perhaps the most controversial stance Tilak took was his opposition to the Age of Consent Bill, which sought to raise the age of consent for girls from 10 to 12 years following the tragic death of Phulmoni Bai, a 10-year-old girl who died after being raped by her 30-year-old husband.

Tilak wrote in his newspaper Kesari that the law was an intrusion into Hindu religious traditions. More disturbingly, he blamed the young girl's death on her physiology, stating:

“The girl had defective female organs. She was a dangerous freak of nature.”

(Source: Wikipedia – Bal Gangadhar Tilak)

Such statements not only show insensitivity but also reflect a regressive attitude that prioritized religious orthodoxy over child protection and human rights.

2. Misogynistic Views on Women’s Role in Society

Tilak was a staunch defender of patriarchal norms and often cited the Manusmriti to justify his positions. He believed that:

“A woman must always remain under male control—first her father, then her husband, and then her son.”

(Source: Vedkabhed.com – Tilak’s Social Views)

He also criticized the British for "liberating" women, seeing it as a disruption of Hindu social order.

3. Hostility to Women’s Education

Tilak opposed the spread of modern education to girls, especially in English and the sciences. He argued that such learning would "de-womanize" them and make them immoral.

“Education in English for women would ruin their traditional virtues and destroy the Hindu household.”

(Source: Vedkabhed.com)

This position directly opposed the work of reformers like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Pandita Ramabai, who fought for women's education and empowerment.

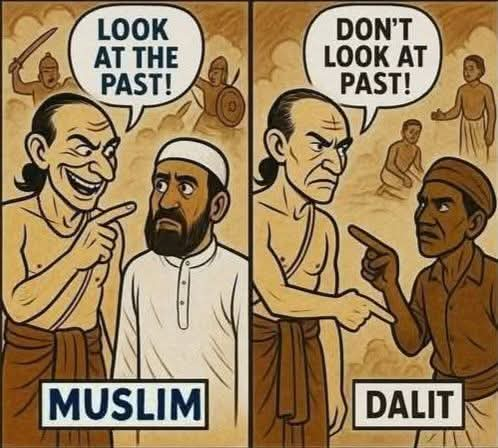

4. Casteism and Opposition to Inter-caste Marriages

Tilak upheld orthodox Brahminical views on caste. He opposed 'pratiloma' marriages (between upper-caste women and lower-caste men), calling them unnatural and likening them to interracial marriages between whites and blacks:

“Just as whites don’t approve of blacks marrying their women, high castes must not allow lower castes to marry their daughters.”

(Source: Padhotoaise.in)

His stance perpetuated caste-based inequality and resisted movements for social justice.

5. Vilification of Social Reformers

Tilak often clashed with social reformers who challenged Hindu orthodoxy. He particularly targeted Pandita Ramabai, a noted social reformer and convert to Christianity. He accused her of using her educational efforts as a front for religious conversion and denounced her as an enemy of Hinduism.

(Source: Padhotoaise.in)

Conclusion: A Legacy of Contradictions

Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s role in the Indian independence movement is historic and pivotal. He was a fierce nationalist who awakened a generation with the cry of “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it.” However, his social conservatism, patriarchal worldview, and casteist ideology must be acknowledged and critically examined.

Like many figures in history, Tilak's legacy is complex—a mix of progressive nationalism and deeply regressive social beliefs. Recognizing both aspects allows for a more honest and nuanced understanding of India’s freedom struggle and its leaders.

Sources: